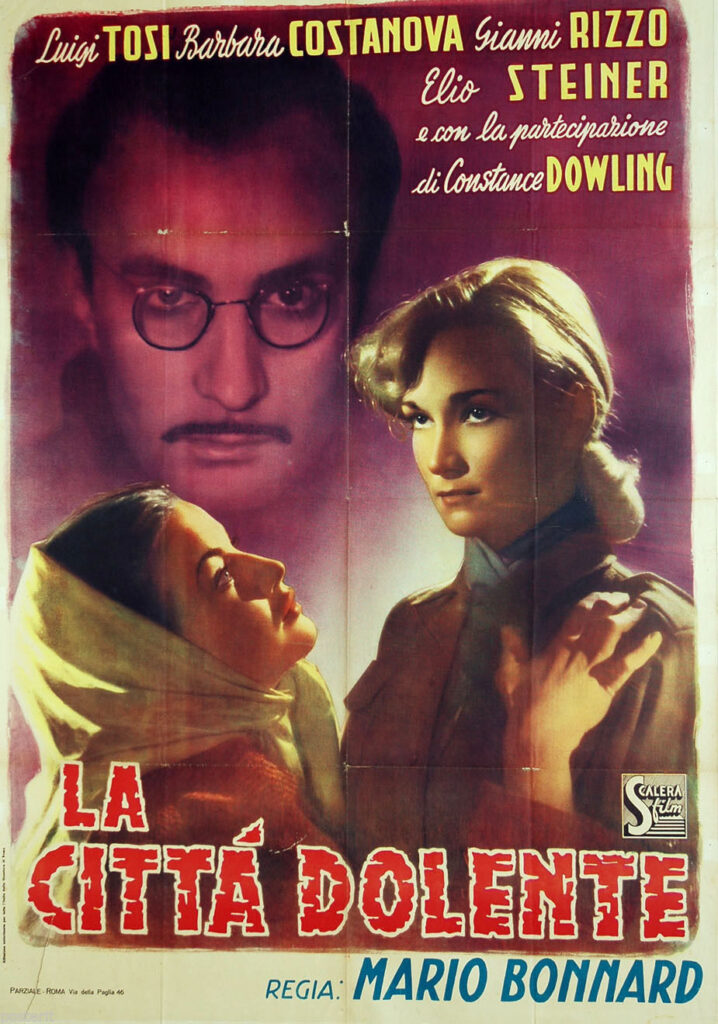

Synopsis

Upon being annexed to Yugoslavia at the Paris Peace Conference in 1947, the City of Pula was evacuated. The protagonist Berto decides to stay because he believes that communism could bring a better future. “La città dolente” (1948), directed by Mario Bonnard, showcases the exodus of Italians from post-war Pula, even though it wasn’t filmed there. It includes archive footage of Vitrotti i Moretti brothers, and Federico Fellini contributed to the script. The film combines documentary and live-action scenes and was filmed almost simultaneously with the events depicted.

details

Original title: La città dolente

Also known as: Grad boli; City of Pain

Year: 1949

Country of production: Italy

Production: Scalera Film

Genre: drama

Directed by: Mario Bonnard

Starring: Luigi Tosi, Gianni Rizzo, Constance Dowling, Barbara Costanova, Elio Steiner, Gustavo Serena, Milly Vitale, Raimondo Van Riel, Attilio Dottesio

Filming locations in Istria: Pula (documentary clips)

Other locations: Rome (Scalera Film – studio)

REVIEW

LA CITTA DOLENTE, directed by Mario Bonnard, 1949

A PAINFUL FAREWELL TO YOUR HOMELAND

In September 1947, in accordance with the 10 February agreements, the City of Pula was definitely annexed to Yugoslavia. As a result, a large number of Pula inhabitants embraced a painful destiny – to become refugees. For those who wanted to maintain their Italian identity, that was also an inevitable necessity. This black and white film, produced by the Italian Scalera, features beautiful shots of the Arena, the Old Town and many dear parts of Pula, and, although shot more than seventy years ago, we have no problem recognizing those locations.

Through the documentary and archive shots from the beginning of the film, made by Enrico Moretti, the symbolic scene of that time, such as the arrival of an Italian journalist to Pula with the instructions of a local man who lets him stay in his apartment - how to throw a key into the sea, while many are packing up and leaving for Italy by ship with large cases that they nail together; this film was given a clear direction. “La città dolente” unveils the tension of Yugoslavian proclamation, ideological indoctrination of the local, mostly Italian population with some new community after the important historical and political change which occurred in 1947 in this region, while analysing the circumstances of the prototypical character of the young hero and his family dynamics.

In addition to the unique socio-historical phenomenon which can be most precisely observed in the context of this area, this approach and treatment of this complex subject matter also emphasizes the idea of the then state which felt great potential in this area, as well as its importance within the newly formed federation, and consequently describes, as the title itself suggests, the pain of the people who had lived in their country until that moment. In the first part of the film, the sequence of images from the daily life introduces the problem, listing the situations which led to what in the second part begins to unravel like a knot of the painful fate of the Esuli.

The story follows a young workman Berto, fascinated by the Italian communist “preachers”. Despite the cries of his wife Silvana, who wants to provide a better life for their son, Berto stays in Yugoslavia because “he convinced me that in several days, things will improve”. Very soon, Berto will regret his decision because of poverty and not-so-much progressive behaviour of the skilfully placed newcomers. And Sergio, an Italian communist who seduces Berto with catchy slogans, whose tragic, enthusiastic fate partly dramaturgically foreshadows Berto’s, with which the film ends, will have the same fate.

After a Party official Ljubica is found in Berto and Silvana’s house by decree, and soon sleeps in Berto’s bed, he manages to force his wife to leave to Italy with their child. Ljubica seduces Berto and wants to turn him into a party propagandist, but after initial hesitation, Berto lashes out at the new regime and ends up in a concentration camp upon Ljubica’s orders. Berto manages to escape to the coast, and upon finding a boat, hopes to be able to make it to Italy. His hopes to join his son and wife are shattered by the machine gun bullets.

In an interview, Federico Fellini described Bonnard as “the one who, above all, seemed a great gentleman, a Roman, a great man from a Rome”. I quote Fellini as one of the screenwriters, together with Anton Giulio Majano, Aldo De Benedetti and Bonnard himself, because of the author’s striving for a kind of lordship, which we read from the film, and which Fellini addresses excellently.

With a certain tendency not so much towards Italianism as towards a bourgeois lifestyle (hence the criticism that the film is anti-communist propaganda), the film’s rhetoric occasionally seems quite infantile, and the characters naive, which may be part of their habitus at the time, which Bonnard wants to highlight.

The aesthetic decision which transforms a Yugoslavian entertainment complemented by a traditional “kolo” into an authentic Bolshoi Theater performance spiced up with tenors and sopranos, three-part choirs, dance pirouettes and a Kazachok is also noticeable. The culture of Pula of that time didn’t know about the elements of “Russian”, so those can be attributed to the artistic decision, that is, highlighting the aforementioned anti-communist propaganda, with attractive elements in the picture which enhance the impression.

Despite that, the atmosphere of the film was extremely well carried out, as well as the topos and the prevailing spirit of Pula newly annexed to Yugoslavia. From a modern viewpoint, this seems almost unimaginable to anyone who moved to Pula after 1947. A large number of political decisions, as well as social movements which have emerged here in the past without ever appearing or being considered possible in other areas of the former Yugoslavia, cannot be fully understood without taking into account the fact that an Italian population had lived here for hundreds of years and, after the peace agreement, was ready to “rather swim across the Adriatic than stay”. This is the first, and in many ways the best feature film about the exodus of Italians from Pula, and it depicts that painful process in a very realistic manner.